|

|---|

The next time David Ellis appears is in the 1860 census in Key West, Monroe, Florida.1

He is listed as being 27. According to his obituary2, he came to America in 1847 or 1848. Since he ceases to appear in the seamen’s registry in Great Britain at that time, it is likely true, although I have been unable to verify that so far, or to determine what he was doing for those 12 years between 1848 and 1860.

|

|---|

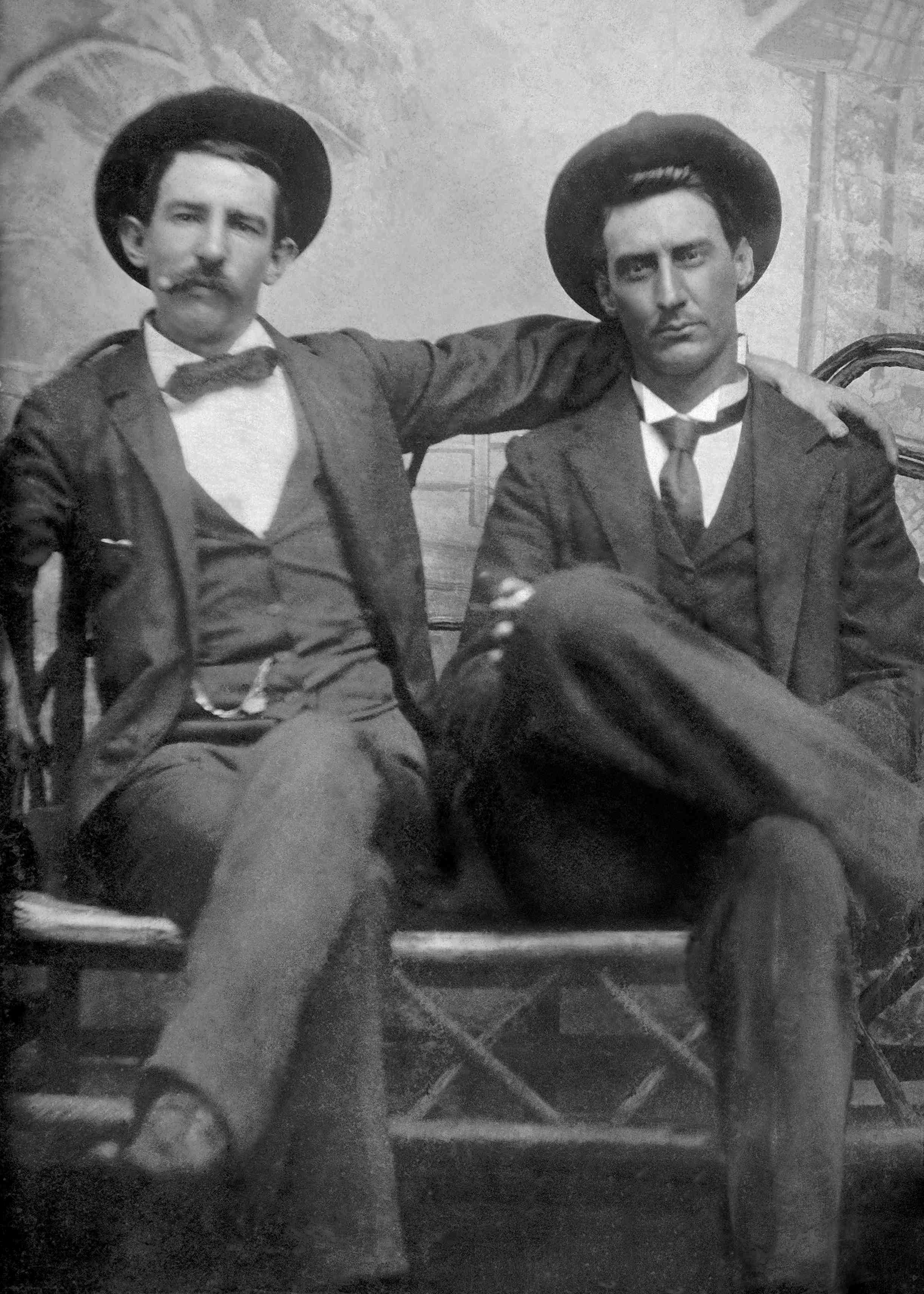

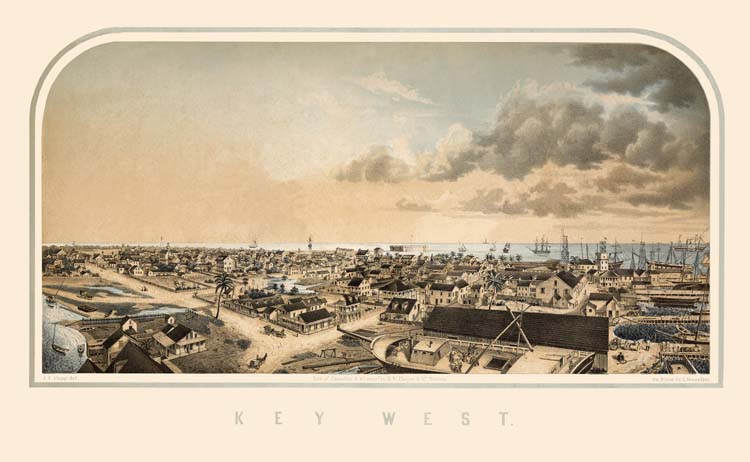

Key West’s unique geographical location has influenced its history from the beginning. What began as a coral reef deep under the sea, over time developed into an island that is approximately 3 ½ miles long by 1 ½ miles wide. Its highest point is 18 feet. It is 160 miles southwest of Miami and only 90 miles north of Havana. One side faces the Atlantic Ocean, the other the Gulf of Mexico. In the 1800s it was the deepest port between New Orleans, Louisiana. and Norfolk, Virginia. It had no fresh water sources. Drinking water needed to be collected in cisterns. It required a skilled captain to navigate the treacherous reefs and tricky currents that surrounded it. What charts existed were sketchy at best and often erroneous.

In 1822 the Secretary of the Navy ordered a survey be taken of the coast and harbor. “From the report of Lieutenant Commander Perry, who was charged with this duty, it has been satisfactorily ascertained that this position affords a safe, convenient and extensive harbor for vessels of war and merchant vessels.”3

In a statement that would come to have a profound meaning in less than 40 years, he goes on to say “An enemy . . . occupying this position, could completely intercept the whole trade between those parts of our country lying north and east of it, and those to the west, and seal up all our ports within the Gulf of Mexico. . . . Commodore Porter’s communications to the department abound in expressions, which show his high appreciation of the advantages likely to

|

|---|

Then in 1825, Congress passed the Federal Wrecking Act, which mandated that

“722. Property wrecked on Florida coast All property, of any description whatsoever, which shall be taken from any wreck, from the sea, or from any of the keys and shoals, within the jurisdiction of the United States, on the coast of Florida, shall be brought to some port of entry within the jurisdiction of the United States. (R.S. § 4239.) Codification R.S. § 4239 derived from act Mar. 3, 1825, ch. 107, § 2, 4 Stat. 133.”5

So in 1828 Key West became a Port of Entry. And the rest, as they say, was history. Since man first ventured onto the waters to transport goods, there have been accidents. Due to the confluence of coral reefs, the Gulf Stream, weather patterns, and the explosion of trade, the area around Key West was littered with the wrecks of once majestic vessels. The wreckers, contrary to what the name implies, attempted to salvage the crew, ship and merchandise, hopefully in that order. However, there are stories that indicate that was not always the case. The merchandise would be auctioned off in an attempt to recoup some of the loss for the owners or insurers of the vessels. “Businessman John Simonton reported in 1826 that ‘…from December, 1824, to December, 1825, $293,353.00 of wrecked property…’ was sold in Key West.”6

The wreckers received a percentage. The first one to the vessel became the master wrecker. He frequently received a larger share. He had control over who else was able to work that wreck. “Ideally, only sufficient cargo should be removed to float the ship free at the next high tide. Often this required the assistance of other wreckers, who would divide a reduced number of shares of the first, or master wrecker. There is a case where a beer-laden ship was salvaged and considerable cargo was consumed in the process. The court decreed no additional fees. In another case, the wreckers consumed considerable food from the wrecked ship and the judge deducted this from the award.”7

|

|---|

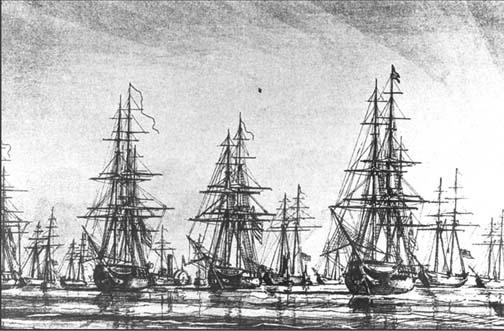

Wrecking offered all a sailor could hope for: an opportunity to challenge his sailing skills against the best, or the worse depending on your viewpoint, that the seas had to offer, with the possibility of getting very rich.

“Those were happy, insouciant days! The wrecker’s life, though full of danger and hard toil at times, was jolly and carefree. Their crafts were well victualed and apparelled, and they would lie all night in safe anchorage, but be under way at daylight to cruise along the reef, on the lookout for vessels in distress. When one was found, as was an almost daily occurrence, it was ‘all hands to work,’ night and day to relieve the ship, before heavy weather would drive her further on the reef, or cause her to bilge. When that catastrophe occurred, the cargo was saved by men working half the time in water up to their middles, and afterwards by diving. This did not mean going down in a diving suit through which the water could not penetrate, but skin-diving, and generally in water impregnated with the component parts of the cargo: sugar perhaps, mayhap guano.

. . .

The richest cargoes of the world, laces, silks, wines, silverware – in fact everything that the commerce of the world afforded – reached Key West in this way.

. . .

A more thrilling sight cannot be conceived than that of twenty or thirty sailing craft of from ten to fifty tons starting for a wreck. As if upon a preconcerted signal, sails would be hoisted, and as soon as jib and mainsail were up, moorings would be slipped and vessels got under way, crowding on all the sail they could carry. The sight of these, dashing out of the harbor, with a stiff northeast wind, bunched together in groups of three or fours, jibbing with everything standing, as they swung around the bend in the harbor off the foot of Duval street, was a scene never to be forgotten. No regatta could match it.”9

Key West was a Mecca for mariners, however I don’t know that this was the draw for David. It is also not clear exactly what the push was that made moving to a foreign county more attractive than his ancestral home and family. I know that “. . . in the coastal villages of Southern Ceredigion the sea continued to attract the male inhabitants . . . There was no other way of life open to them and going to the sea was regarded as a means of evading the abject poverty of home. . . . Southern Cardiganshire vessels became ever more concerned with the deep-sea trade and voyaged between large ports the world over. Ships that originated in even the small villages of the Cardigan coast – Aber-porth and Llangrannog – were concerned with sailing to distant ports.”10

I trust future research will disclose the reasons David ended up in Key West. I present a broad-stroke view of a possible explanation. With time I hope to develop a definitive account of his movements.